Data published this Wednesday by the European Central Bank show clear signs of recovery for the Eurozone. The measures taken by European politicians during the last months seemed to have reassured the markets as a breakup of the Eurozone is becoming more and more unlikely. Are we out of the woods yet or are the latest numbers just a momentary pike in what still seems to be the world’s most volatile economic area?

A report by the ECB saw the M3 index, the bank’s preferred indicator of Europe’s health, rise by 3.9% – the fastest rate since early 2009. M3 describes the broad money supply in the member states and shows a clear upwards trend. Europeans have put €105 billions into their bank accounts and managed to take off a lot of pressure of the troubled financial sector. Although the findings seem to suggest that Europe’s “core” countries – Germany, France and the Netherlands – were mainly responsible for that sharp increase it also testifies that deposits have increased in Ireland and Greece which might indicate that the worst part of the crisis is overcome. At the same time M1 that focuses more on economic output has risen by 6.2%, its fastest since September 2011.

“Why now?”, some of you might ask. Of course, there is no clear answer to this question but a strong commitment to the single currency has certainly not done any harm to the state of the euro. The ECB was a central figure in this scenario and Mario Draghi’s declaration to do “whatever it takes” to prevent a breakup of the euro zone still stands out as one of the most memorable statements in the political debate.

And indeed, Draghi has done quite a lot recently to soothe the markets and send the right signals to investors. The press conference of the ECB on September 6th where the “outright monetary transactions” were presented to the public marked a turning point for the future of the continent. Dubbed as “unlimited bond buying” by the financial press, the new plan brings about some massive changes for all the actors involved – mostly for the ECB itself. While the OMTs are still linked to macroeconomic adjustment programmes (“bailouts”) and therefore new austerity measures for troubled states, the central bank agreed to give up its seniority status as a creditor. This means that in case of failure of any troubled state, they would not get a preferential treatment concerning their debts and are on par with private investors. This has massively restored trust in the single currency and saw both bond interest rates fall to new lows in Spain and Italy. The support of the euro has evoked outrageously positive reactions by the market but was not the last step in the seemingly neverending quest to save our currency.

Although a third Greek bailout was vehemently denied on the press conference in September, today it is only a question of time. And nobody even seems to care anymore. Even protests in Germany that called the ECB’s decision and “an economic disaster” only three months ago have ebbed away and analysts agree that the new billions for Greece will be nodded off without further objection.

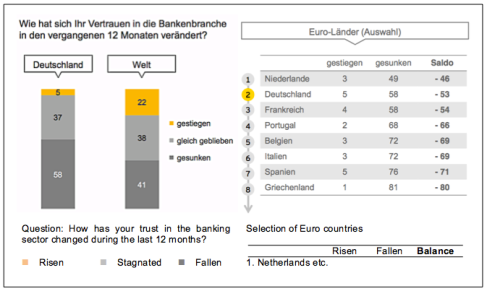

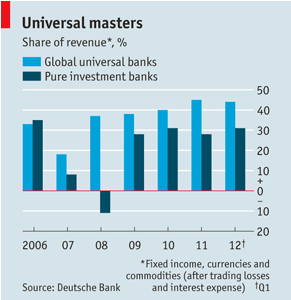

What implications does this have for the banking sector then? Banks at the moment are trying their best in order to survive. One would argue that this should make them rethink their business models, but realistically speaking, radical changes in times of crisis are most unlikely to happen, if they are not forced. I have mentioned before that I am quite opposed to the bail-out-no-matter-what policies that seem to have been employed recently. Just yesterday, Spain’s banks were bailed out with 37 billions. But here in Europe this is a question of saving a single market that is essential for the world economy. By relaxing the markets and letting economic agents know that politics won’t fail them, we give them more room to act and to finally make some decisions that have the potential to be more sustainable in the long-run. We should hope so at least. With Europe’s banks now finally having a more stable future, we should expect them to have learnt some lessons from the crisis. And hope that it is really all about to change in the near future.